Barcelona, in order to face the waves of immigration that have defined it, had to carry out various urban activities over the course of the past century. It was about creating complete neighbourhoods that met minimum liveability requirements and providing services for people with limited economic resources. A good example of this is the affordable housing in Sant Andreu, a neighbourhood now integrated in the urban sprawl that, when they were built, was separated from any urban nucleus, on cheap land next to the Besòs River.

Les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor abans dels enderrocs de l’any 2007.

With the intention of maintaining some vestige of the lifestyle of the popular classes that have inhabited this area while developing a new urban plan, the administration decided to demolish the neighbourhood to build newer, bigger buildings, keeping only one block of these single-story homes to make a centre for public facilities and a museum on the affordable housing.

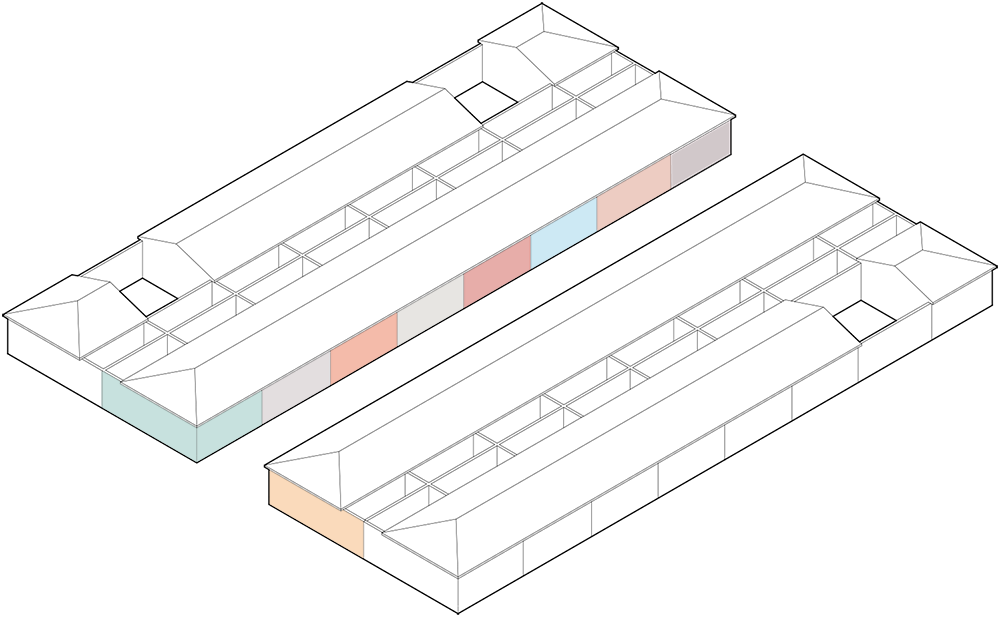

Axonometria del conjunt museïtzat. Tractament dels dos blocs i el seu carrer central com una unitat.

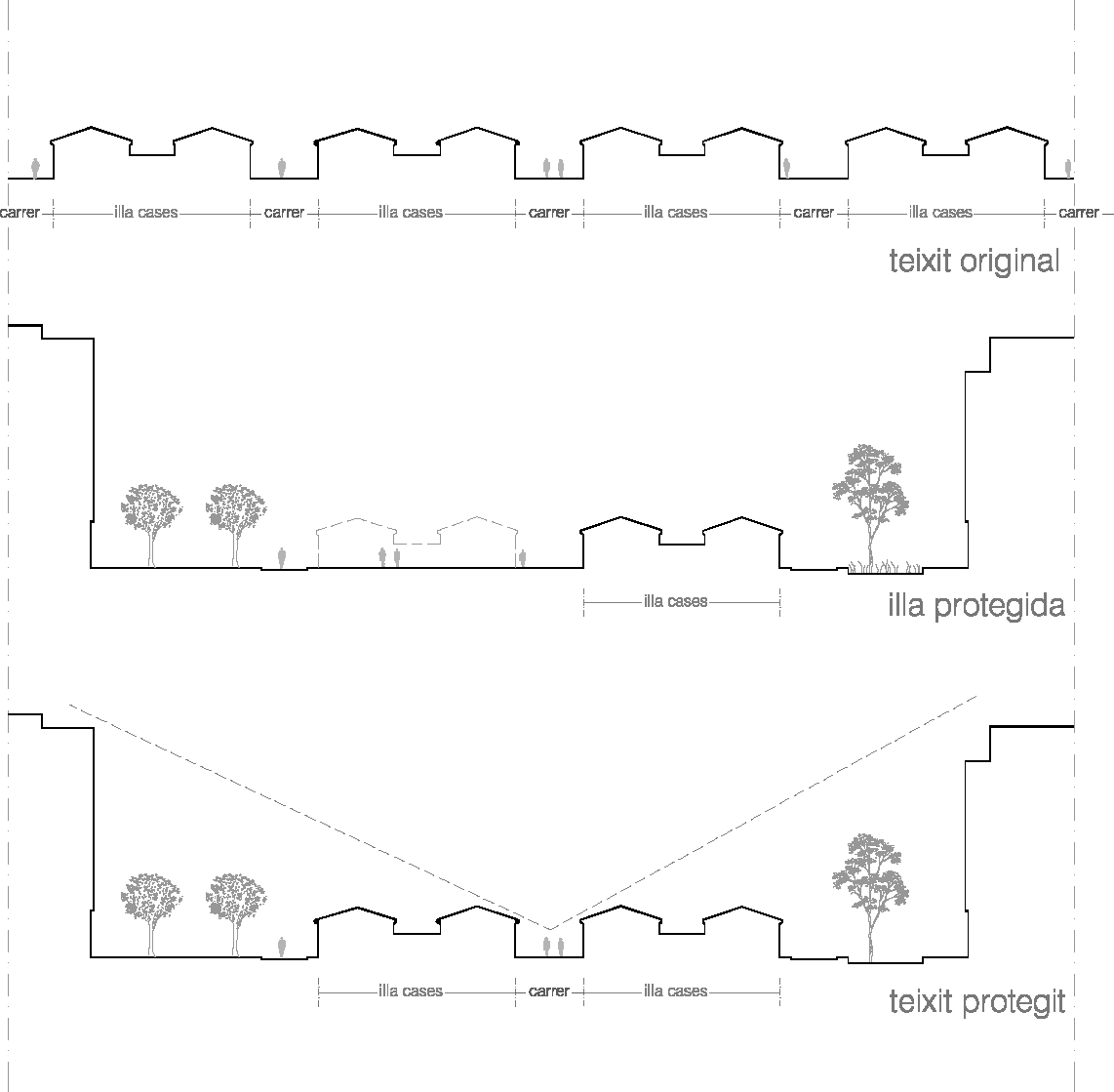

Together with Harquitectes, we participated in the tender to come up with a project to maintain that small space of remembrance, but changing one of the administration’s proposals. Instead of maintaining a single block, we proposed keeping two –adjusting the price so that it is not more expensive– with the desire to preserve the street.

Variació de l’àmbit d’actuació: d’illa protegida a teixit protegit.

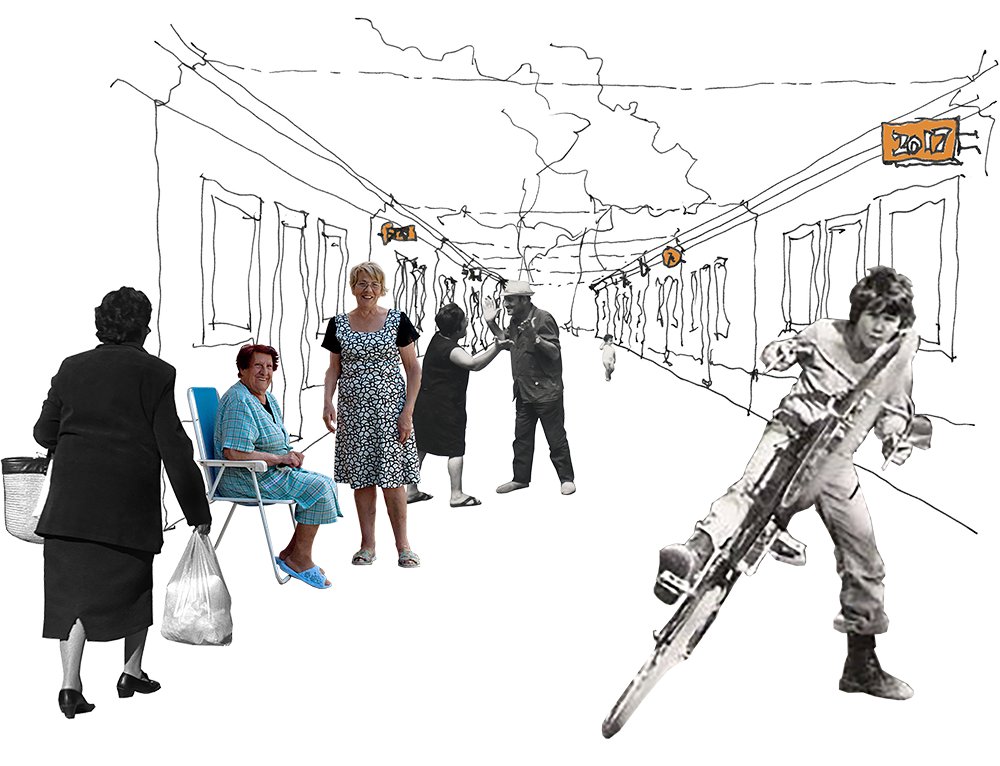

This is a basic element if you understand what cheap houses were. These are very small houses and therefore tenants have always used the street not only as a place for socialising but as part of the home itself. In the houses that are still inhabited, it is common to find neighbours with chairs in the doorway. Making a museum of only the housing is a mistake because residents’ lives cannot be explained without the street outside. The street must therefore become a public space, but also part of the museum.

El carrer com a eix estructurador de la vida del nou equipament.

Another key element to bear in mind is that if the museum hopes to represent the lifestyle of the area’s inhabitants by preserving three houses and staging them to represent different points in history, all three must be preserved and the access from the central street maintained. The historic indoor elements are part of a task that is not the goal of the tender, but the preliminary step –demolition and conservation– also must take into account how it will be used later.

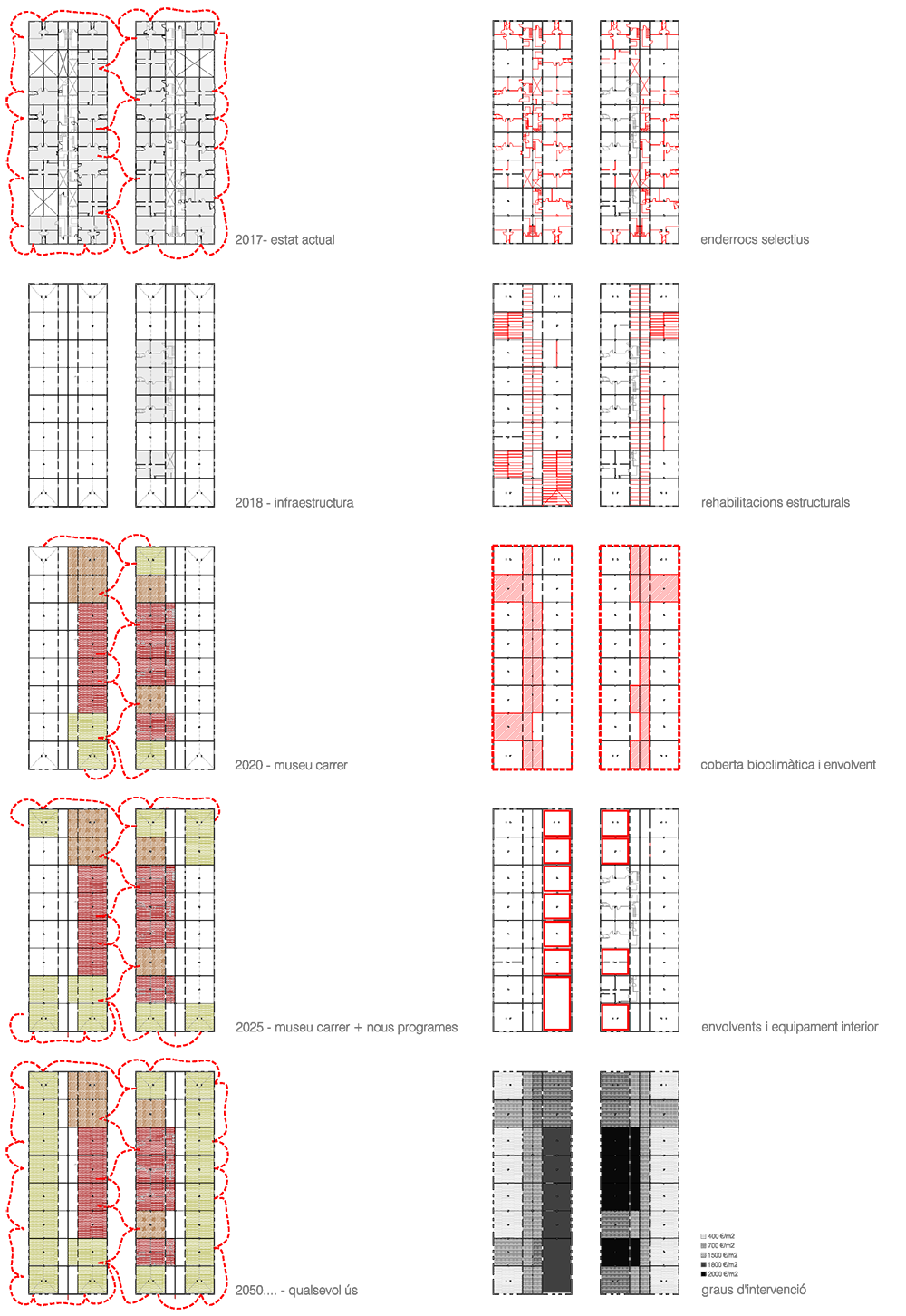

Part de les cases de l’illa seran enderrocades mantenint la façana.

The remaining houses on the block will be demolished, keeping only the façades. Therefore, we will generate large spaces with only the elements necessary to preserve the structure. However, they will not make up a uniform space, but, since the preserved houses do not necessarily have to be contiguous, we will generate a wide space with a form that adapts to the non-demolished spaces. By doing so, we will create corners that may be adjusted according to the use assigned to the facility. Even so, it is necessary to consider the relevant architectural elements as heritage and, therefore, we propose keeping some elements in the facility/building, with only selective demolition.

Evolució dels usos i propostes d’intervenció.

Eventually, it has to be taken into account that the architectural intervention will have a clear impact on the museum that will be created later. Our position gives it a certain museum-focused meaning, because it valorises the street and preserves the original value –and the narrowness– of the houses along with other significant heritage elements. Thus, although museum curation always involves recreation, we try to faithfully preserve the lifestyle of the people who inhabited the affordable houses over time.

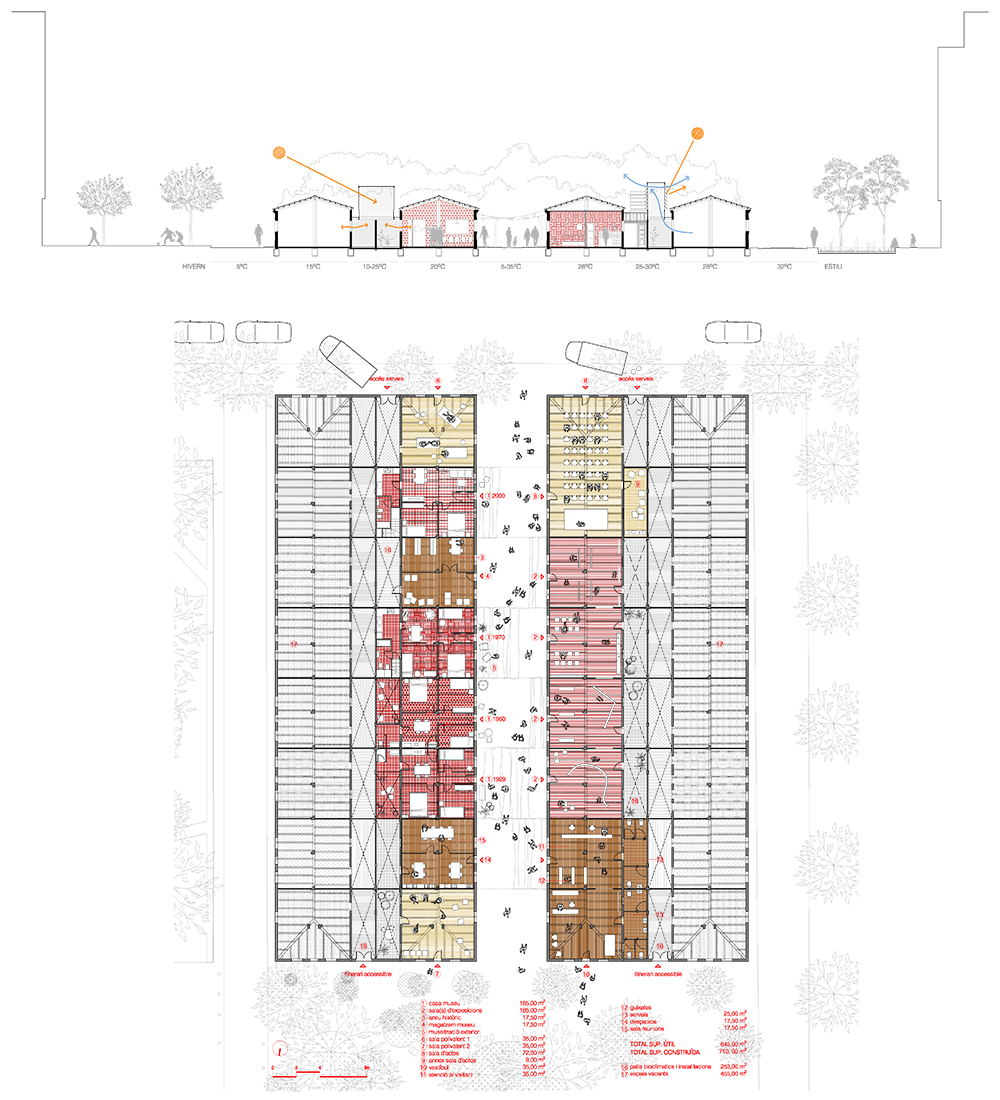

Planta i secció de la proposta de museïtzació.

Les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor.

Les Cases Barates del Bon Pastor.